CAR-T Tx Shifts into First Gear in Lung Cancer

by Shamali Pal for Medpage Today

Overview by Dr. Jennifer Cipriani, EGFR Resisters member.

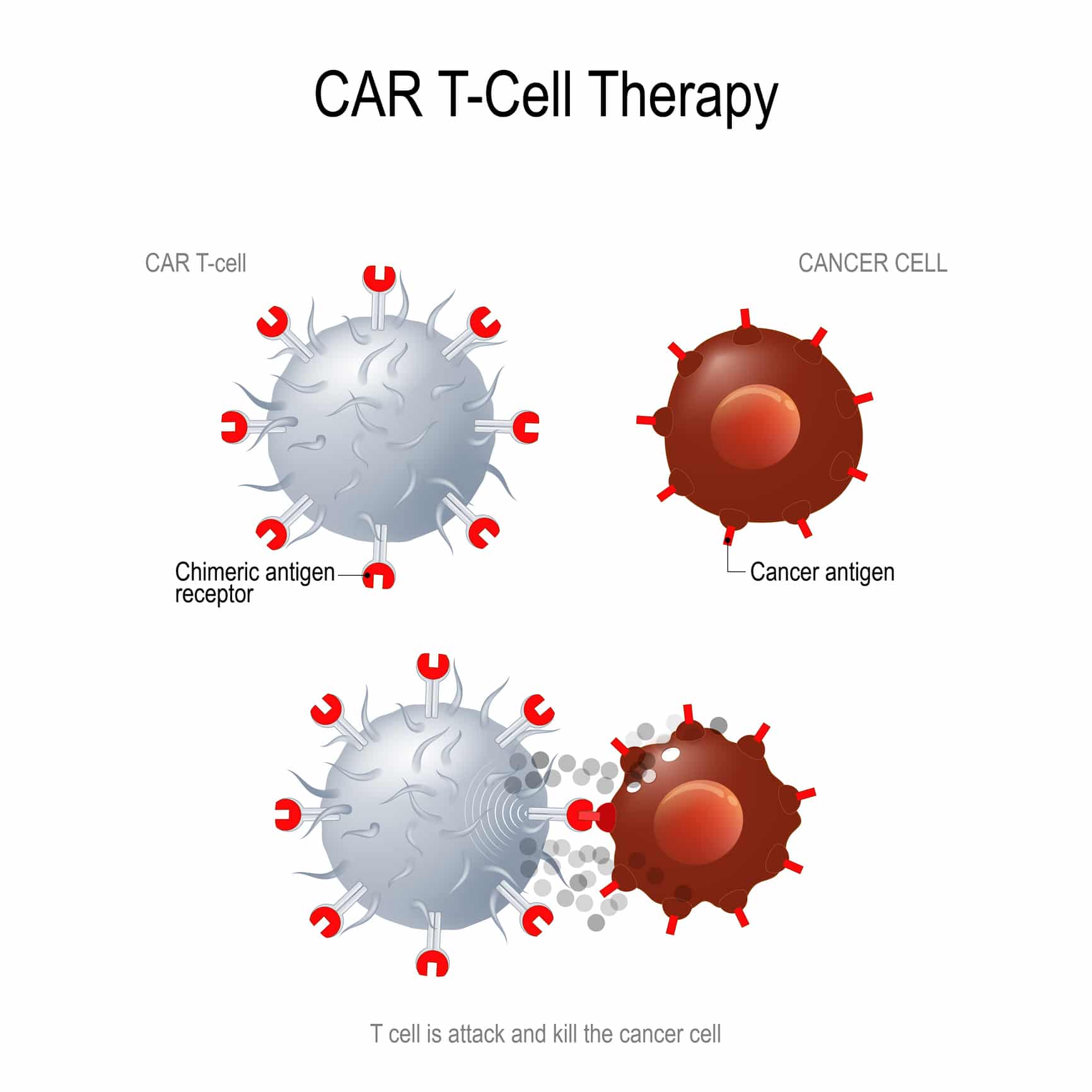

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has been in the news a lot in recent years, mostly for it’s success in treating blood cancers. CAR-T therapy has shown great promise in extending survival in previously incurable forms of leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma. The hope is that researchers can find equal success in treating solid tumors in the near future.

So what exactly is CAR-T therapy?

CAR-T is a type of treatment in which a patient’s T cells (one of the smartest and most important cells in the fight against cancer) are removed from the patient’s blood, modified in the lab to make them more likely to attack the patient’s own cancer cells, and then given back to the patient by infusion. A gene for a special receptor that binds to a certain protein on the patient’s cancer cells is added to the patients T-cells in the laboratory. The special receptor is called a CAR. When the CAR is added to the patient’s T-cells, large numbers of the CAR-T cells are grown in the laboratory and given back to the patient by infusion. The idea is that these engineered T-cells will now recognize the tumor and attack the cancer cells. Treating cancer this way is more specific and potentially even more potent than chemotherapy.

It is still unknown whether CAR-T can have the same impact on tumors of solid organ origin. Many researchers are working hard at this very moment trying to answer this very question. Scientists and researchers are trying to use what they’ve learned from using CAR-T in the treatment of childhood leukemia and attempting to apply those principals to the treatment of solid tumors. The difficulty comes in trying to target the tumor while avoiding toxicity to the patient. According to Dr. Alastair Greystroke of the University of New Castle in England, “There are clinical trials starting for the new generation of CAR-T cells in solid tumors, including lung cancer, which are targeting a number of different known tumor antigens.”

According to the review, a search of ClinicalTrials.gov using the search terms lung cancer and CAR-T cell returns multiple studies, more than half of which are being conducted in China. The majority of these trials are in the recruitment phase. In the U.S., CAR-T trials including lung cancer are planned at the NCI, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and the University of Washington in Seattle. These trials are enrolling patients with specific protein markers on the surface of their tumor cells.

For instance, the trial at the University of Washington (Genetically Modified T-Cell Therapy in Treating Patients With Advanced ROR1+ Malignancies) is a phase I trial looking at the side effects and best dose of genetically modified T-cell therapy in treating patients with receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 positive (ROR1+) stage IV advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that has spread to other places in the body and usually cannot be cured or controlled with treatment. Potential patients must have ROR1 expression in > 20% of the primary tumor. Genetically modified therapies, such as ROR1-specific CAR T-cells, are taken from a patient’s blood, modified in the laboratory so they specifically may kill cancer cells with a protein called ROR1 on their surfaces, and safely given back to the patient after conventional therapy. The “genetically modified” T-cells have genes added in the laboratory to make them recognize ROR1.

One of the best challenges facing researchers is the potential for the engineered T-cells to attack cells other than the tumor cells. If the tumor-associated antigen to which the CAR is targeted also exists on other cells (ie normal tissues) then those tissues are at risk of being attacked and damaged resulting in toxicity for the patient. CAR-T cells may also damage normal tissues by cross reaction with a similar protein on the surface of the normal cells. One major concern is the so-called cytokine release syndrome (CRS) which presets as a “constellation of symptoms including fever, low blood pressure and also potentially neurological and other organ dysfunction”. It is caused by the release of a substance called cytokines and can be very serious and life threatening. This is obviously a major concern and the management of such toxicity is of utmost importance in allowing CAR-T therapy to become more widely used. Another major issue is cost. The 2 FDA-approved CAR-T therapies each cost a minimum of $400,000 per patient.

Many of the obstacles seen in CAR-T therapy in solid tumors are quite different from hematologic malignancies. Scientists have to ensure that CAR-T cells are able to travel to the bulk tumor sites, survive the tumor micro-environment, and persist for a long time so that they will be effective in both the short and long term. All of these trials together constitute that first step in the development of future CAR-T trials that may benefit lung cancer patients.